Table of Contents

The idea of sustainability may sound abstract and idealistic, but in the case of farming, it's eminently practical. Our ability to grow food depends on the ecological health of the landscape we grow it in. If our farming depletes and damages farmland, we won't be able to keep doing it indefinitely.

So we have a responsibility to ourselves and our descendants to find methods of producing food that minimize damage to the farm ecosystem—or better yet, that regenerate and replenish it. Below are four key practices that are helping 21st-century farmers do their work sustainably.

A landscape approach

Farms are not isolated from one another or from the natural systems around them, and they function best when that is taken into account. Recent research has shown, for example, that uncultivated areas on and near farms—including trees, shrubs, and grasses at the edges of crop fields and along streams—can serve as resources for farmers. By fostering biodiversity and providing habitat for pollinators and other beneficial wildlife, such as birds, bats, and bees, uncultivated areas can boost farm productivity and reduce costs.

Researchers recently estimated that the loss of uncultivated habitat near farms in the Midwest has increased the use of insecticide needed to control pests by an amount that would cover some 5,400 square miles of crops (see figure below). In addition, streamside woodlots on and near farms serve to buffer waterways from erosion and polluting runoff.

Farmers can also improve their operations by partnering with neighboring farmers to share and conserve resources. The University of Maine Cooperative Extension has had success pairing dozens of farmers on thousands of acres for innovative collaborations—swapping livestock manure for feed crops, integrating cropping systems, and sharing equipment—that have led to environmental improvement and increased farm profitability. Such cooperation could generate similar benefits anywhere agricultural diversity exists.

Crop diversity and rotation

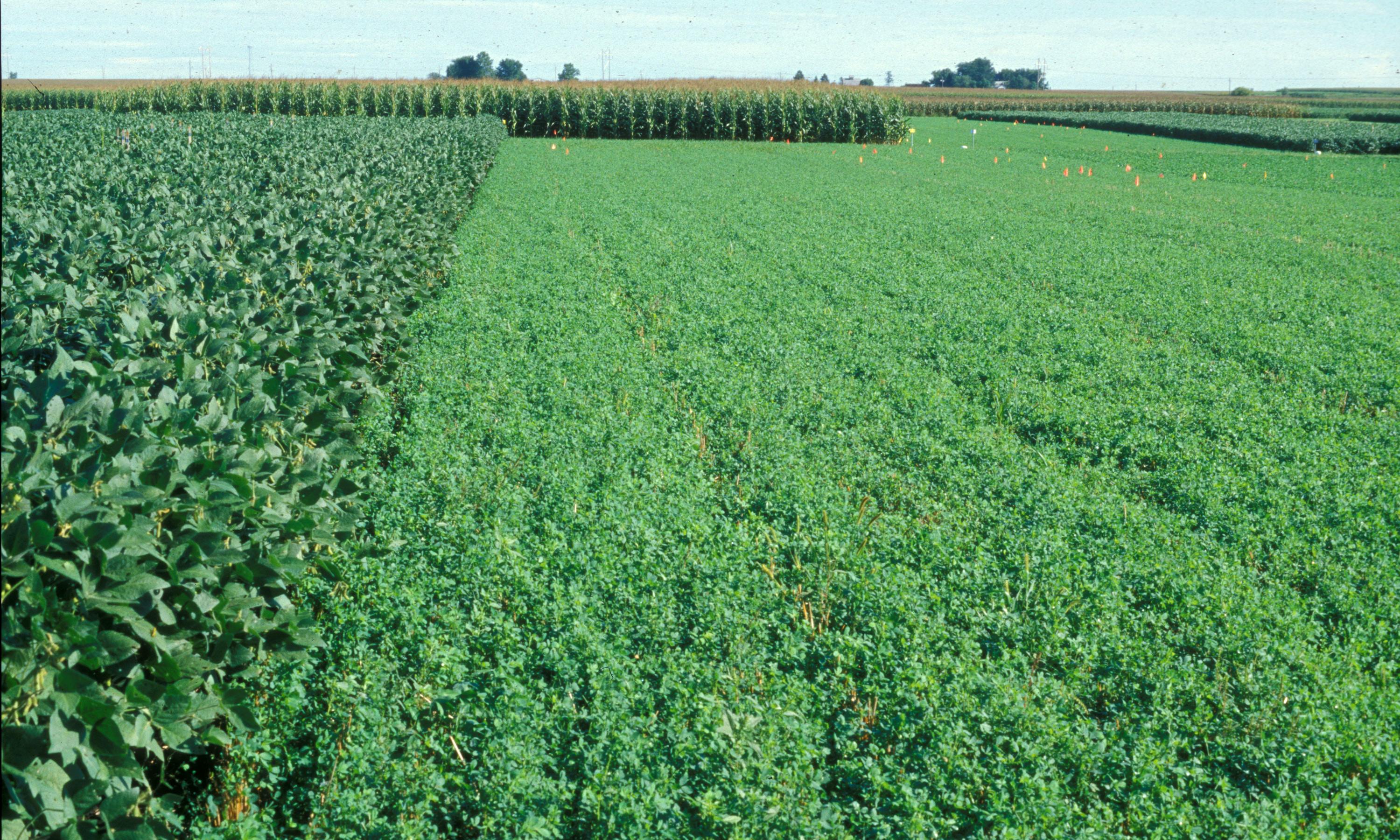

Agriculture in the U.S. Midwest is dominated by two crops—corn and soybeans—grown continuously or in simple rotation, a trend that may have worsened in recent years. The most important change we could make to move toward a healthy, sustainable food system would be to grow and rotate a variety of crops including wheat, oats, alfalfa and other legumes, and sorghum in addition to corn and soybeans.

Growing a greater diversity of crops would allow farmers to reap the environmental and energy advantages of longer, more complex crop rotations. Recent research has demonstrated that multi-year, multi-crop rotations produce high yields for each crop in the rotation, control pests and weeds with less reliance on chemical pesticides, and enhance soil fertility with less need for synthetic fertilizers.

- Pests and weeds. Because most pests are adapted to thrive on only a limited number of crops, a crop rotation that includes non-host crops will drive down their numbers. Reduced use of chemical pesticides, in turn, encourages beneficial organisms such as soil fungi, pollinators, and predatory and weed-seed-eating insects and spiders that further reduce the need for pesticides, which benefits the environment and saves farmers money. Recent long-term research in the heart of the Corn Belt has shown that integrated weed control based on smart crop rotations can reduce the need for fertilizers and herbicides by 90 percent or more, while maintaining high yields and farm profits.

- Soil fertility. Rotations that include nitrogen-producing legumes such as peas, beans, and alfalfa provide subsequent crops with substantial amounts of this critical nutrient. And recent research shows that nitrogen from legumes remains in the soil longer than the nitrogen in synthetic fertilizers, leaving less to leach into groundwater or run off fields and pollute streams.

In addition to grain and forage crops, the climate and exceptionally rich soils of the Midwest are well suited to a number of other crops including vegetables and fruit trees. While few now remember it, a century ago at least 10 food crops were grown commercially in Iowa, including potatoes, apples, and cherries. Bringing back such crops, especially sought-after heirloom and specialty varieties, represents an opportunity to market foods that could be branded based on their place of origin and sold at premium prices.

New additions to the rural landscape could also include bioenergy crops such as perennial grasses. These so-called cellulosic feedstocks can be grown on marginal land, enhance soil fertility by promoting the growth of various soil organisms, and provide a climate- friendly source of energy (their deep roots and long lives enable them to keep more carbon out of the atmosphere than annual bioenergy crops such as corn, whose growth is typically assisted with carbon-intensive fertilizers and pesticides).

Cover crops

On many farms in the United States, fields are left bare when crops are not growing—often for much of the year—creating a number of problems. Wind, rain, and snowmelt erode the bare soil, and nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers leach into groundwater or run off into streams and rivers.

This loss of soil and nutrients adds costs for farmers and causes severe—and expensive—environmental and public health problems in agricultural communities and beyond.

Some farmers grow plants known as cover crops to protect and build their soil during the off-season, or for livestock grazing or forage. Commonly planted cover crops include hairy vetch, annual ryegrass, and crimson clover.

If adopted widely, this underutilized practice could help solve many environmental and health problems associated with bare soil. And because cover crops add organic matter to the soil, they can help farmers maintain the long-term productivity of their land.

Despite these potential benefits, cover crops are currently planted on only a small fraction of U.S. farmland. Why? Substantial economic and technical barriers—some embedded in government policies—discourage farmers from growing them. New or modified policies that promote cover crop adoption, on the other hand, would enable farmers, taxpayers, and communities across the country to reap the benefits.

Integrating crops and livestock

U.S. livestock production was once conducted on the same farms that grew feed crops, but over the past half-century, most livestock have been removed from that setting and consolidated into enormous CAFOs (confined animal feeding operations) that produce far too much manure to be distributed as fertilizer economically (since crop fields are often too far away). Instead, the manure spills from lagoons, runs off fields, or leaches into groundwater—transforming the nutrients in manure from the valuable resources they could be into dangerous pollutants.

The current situation is considered economically efficient only because livestock producers can ignore the societal costs of pollution and the lost value of manure in their calculations.

Plant and animal agriculture can be reintegrated in several ways. Some livestock, especially beef cattle and dairy cows, could be raised partially or entirely on pastures, which (when well managed and not overstocked) would reduce soil erosion, increase soil fertility, store carbon, and provide habitat for beneficial organisms. Pasture-raised livestock also require fewer antibiotics than those raised in CAFOs, reducing their contribution to the spread of antibiotic-resistant disease. Furthermore, pasture-based and other integrated livestock operations offer midwestern farmers the opportunity to meet rising consumer demand for healthy, humane, grass-fed, and sustainably raised meats and milk.

Crop and livestock reintegration can be accomplished on a regional basis or on individual farms; distributing animal operations throughout the Midwest would produce a range of benefits, from reduced nutrient pollution to enhanced soil fertility. And integrated livestock production would support local markets for forage crops such as alfalfa, helping to facilitate longer crop rotations and conservation practices in the region.