US health and environmental policies currently regulate one pollutant and one source of pollution at a time. But in the real world, no one is exposed to one pollutant from one source at a time. Rather, we are all exposed to a multitude of harmful chemicals through a number of pathways—from the products we use in our homes and workplaces, to sources of pollution in our neighborhoods, to legacy pollution, often driven and exacerbated by systemic racism and unjust public policies. These chemicals can accumulate in our communities’ water, soil, and in the food chain to cause more harm than the individual pollutants would alone.

What are Cumulative Impacts?

Cumulative impacts describe the multiple exposures to pollutants and sources of pollution to which we are continuously subjected. To understand cumulative impacts, consider the analogy of a doctor’s appointment. You might go to a clinic for a sore throat, receive a quick strep test, and then be sent home with antibiotics. That’s essentially how most environmental protections work, addressing one issue at a time. Such an approach can work adequately, but only if you have access to healthcare in the first place, have no underlying conditions that might signal additional complications, haven’t had recurring strep infections, and don’t have other issues to treat such as a sprained ankle or frequent headaches.

By contrast, a regulatory decision informed by cumulative impacts would require your doctor to consider your full medical history, to coordinate treatment to make sure that you didn’t get sent to four different clinics; to consider medication interactions and to offer a broad enough series of tests to make sure you left the appointment as healthy as possible.

In environmental decisionmaking, we often have overwhelming evidence that we’re facing more than the equivalent of a simple strep throat infection. That’s why we need to take a broader, more systemic approach.

Find Out More in Our Cumulative Impacts Toolkit

Discriminatory Policies

When it comes to pollution, a root of the problem is that decades of racially discriminatory policies and practices from the federal to local level continue to influence where sources of pollution are located. The policy known as “redlining” offers a good example. In the 1940s, the US government made maps to inform mortgage lending practices in local real estate markets across the country. These maps actually designated areas with larger proportions of people of color as more “hazardous” (often marking them in red, hence the name redlining). Even today, these policies continue to impact zoning and permitting decisions and are at least partially responsible for the fact that so many industrial sources of pollution and major roadways lie in close proximity to communities of color.

The bottom line is this: Due in large part to a history of discriminatory practices, sources of environmental pollution are not evenly spaced and they do not operate in isolation. To adequately protect public health, our environmental regulatory system needs to reflect these realities.

What are Cumulative Impact Policies?

Cumulative impacts policies seek to address, and ultimately eliminate, historically unfair burdens of pollution by considering real-life exposures, reducing stressors on community health, and taking a more holistic approach to environmental decisionmaking. There is a growing body of science to support the need to address the harms from exposures to multiple pollutants from multiple sources that accumulate over time. Here are some of the key concepts involved:

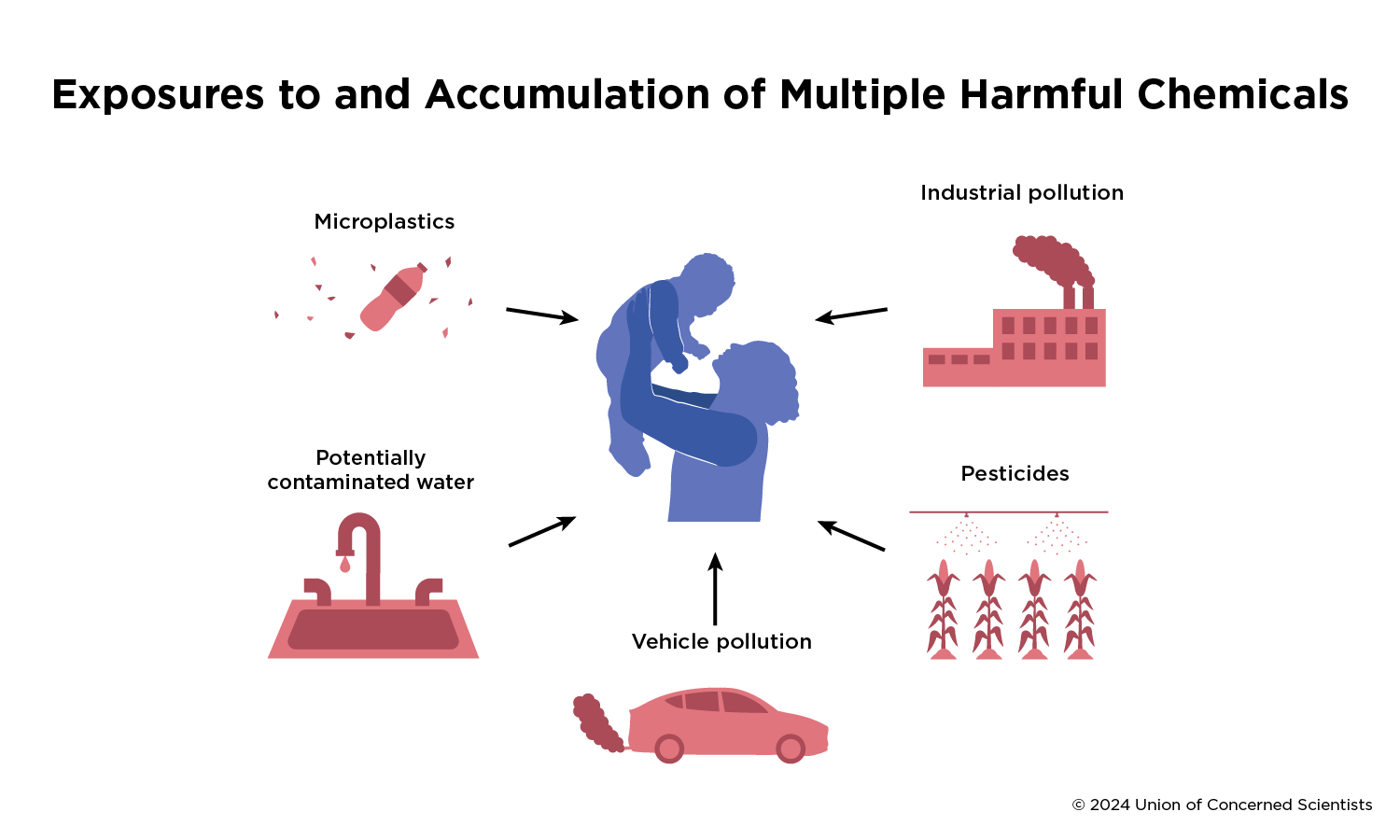

People are exposed to multiple chemicals

Exposure science studies the extent to which humans come into contact with environmental factors, including chemicals. Scientists measure exposures with tools like air sensors, among other methods. An individual’s exposures to pollutants over the course of a lifetime is called the “exposome.” Multiple chemicals and compounds can be measured in individuals as biomarkers that change over the course of their lives and there are detectable levels of many different chemicals in the US population from these environmental exposures.

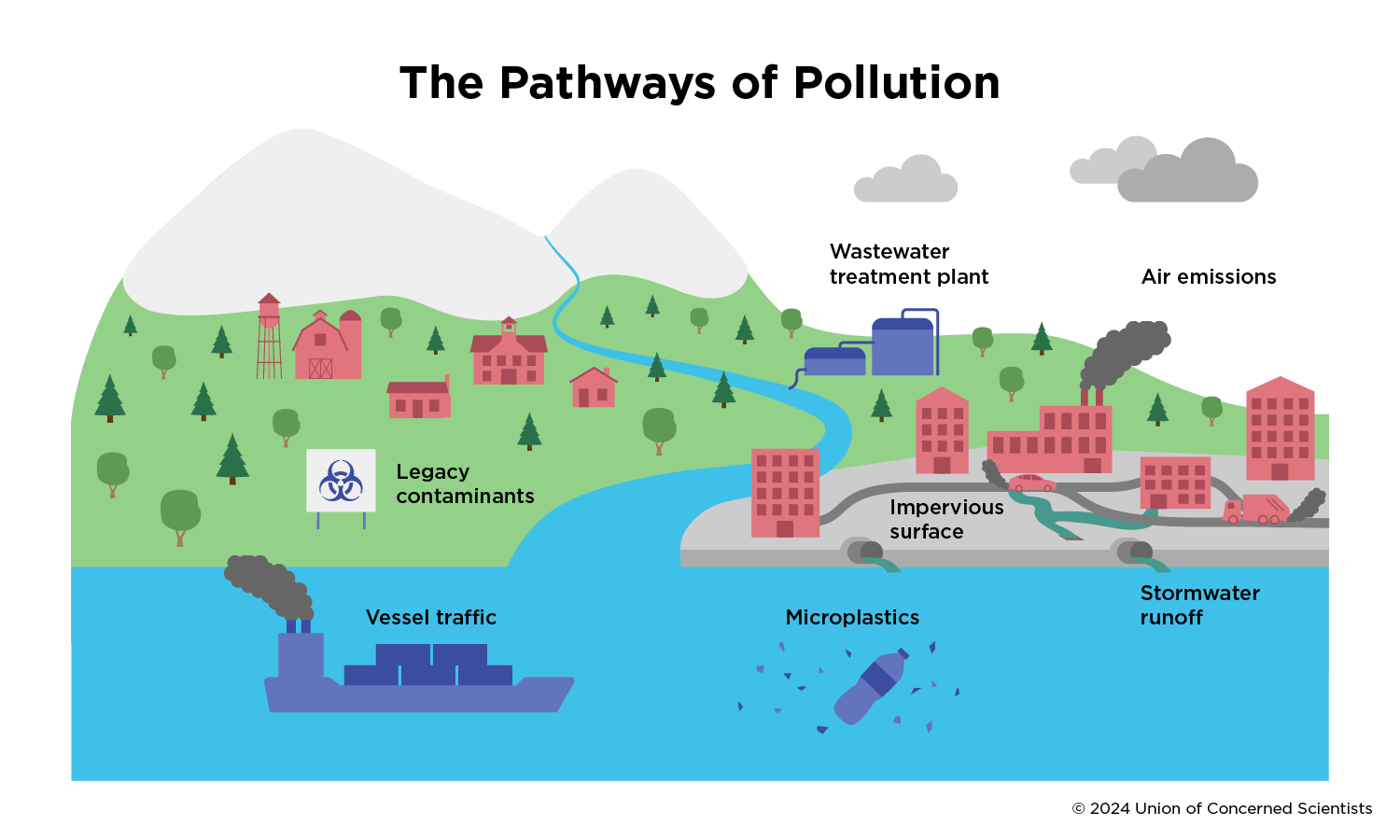

Exposures occur via different pathways

Exposure scientists have documented that people come into contact with environmental chemicals through contact with skin, ingestion, and breathing, and by studying the combination of all these pathways they have been able to better understand these exposures.

Pollution is not equally distributed

Scientific studies that analyze the geography of pollution sources and people, using data from the United States Census, have repeatedly shown that pollution is not equally distributed geographically or in the US population. More often than not, a higher pollution burden has been measured and modeled in low-income communities and in communities of color. In the United States, more than half of the people who live within three kilometers of a hazardous waste facility are people of color. Moreover, scientists have found that the pollution exposure disparities are more extreme in areas where there is more racial residential segregation.

Pollutant Accumulation

Pollutants enter our bodies and are then metabolized or eliminated by breathing, sweating, or via other processes. Pollutants that remain in people’s bodies are sometimes referred to as a “pollutant burden.” Our bodies hold onto some pollutants for longer time periods, and sometimes pollutants accumulate over time (a process known as “bioaccumulation”). We also may eat animals or plants that have accumulated pollution through the food chain (a process known as “biomagnification”).

Exposure to mixtures can be worse than exposure to single chemicals

Many scientists have found that doses of multiple chemicals can have different and sometimes greater adverse impacts than doses of individual chemicals alone (some examples include studies on: endocrine disrupters, carcinogenic impacts, and neurodevelopment). Today in the United States, chemicals are normally regulated by comparing an individual chemical exposure to a level that has been found to have little to no impact within a margin of safety, such as a "No Observed Adverse Effect Level." But, there is evidence showing that exposure to multiple chemicals—all individually beneath these thresholds—can have an overall impact greater than what would be expected in an additive response.

Chronic stress and social adversity can worsen outcomes from chemical exposures

Humans vary in how they are impacted by chemical exposures. This variability can be driven by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. There is some evidence that populations with adverse social conditions have worse outcomes or longer recoveries from environmental chemical exposures. In other words, chemical exposures together with psycho-social stress, socio-economic status, noise, racial disparities, and lifetime trauma among other factors, have been associated with worse health outcomes compared to chemical exposures alone. There is scientific support and existing methodologies for taking real-life human variability into account in assessing effects from multiple environmental, social, and economic stressors.

Find Out More in Our Cumulative Impacts Toolkit

Time for a More Holistic Approach

While there is much more work to be done, environmental justice organizations and community groups, as well as local and state units of government have made significant progress towards a system that addresses cumulative impacts. The past several years have seen a number of important developments in the area of cumulative impacts at both the state and municipal level.

California developed a program called CalEnviroScreen that integrates multiple environmental and health burdens to inform the state’s resource allocation. In Minnesota, grassroots and neighborhood organizations helped press the state legislature to pass a law in 2023 requiring consideration of cumulative impacts in the permitting process. Responding to decades of tireless and strategic advocacy, the New Jersey legislature passed a statewide Environmental Justice Law that requires the state’s department of environmental protection (NJDEP) to evaluate environmental and public health impacts of specified facilities on overburdened communities when reviewing permit applications. Other states are now in the process of following suit, including Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New York.

To address and ultimately reverse longstanding health inequities, we need a regulatory system that addresses at least some aspects of cumulative impacts at the federal level. That means continuing to urge federal agencies to listen to their environmental justice advisors such as those at the National Environmental Advisory Council (NEJAC) and the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council (WHEJAC) as well as to external environmental justice experts. Together, we can work toward a framework that includes cumulative impacts policies as a vital tool to ensure that our pollution policies equitably protect everyone.

Find Out More in Our Cumulative Impacts Toolkit