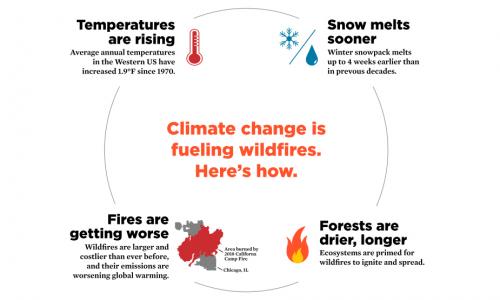

There is a strong connection between climate change and wildfires. Wildfire activity in the United States is changing dangerously, particularly in the west, as conditions become hotter and drier due to climate change. Past forest and fire management practices often exacerbate wildfire risk. Development patterns can both increase people exposed to wildfires and increase ignition sources that spark fires.

How do we know that climate change plays a role in the increasingly powerful wildfires? Although fire has always been a natural—and beneficial—part of many ecosystems, climate change and other human-caused factors are fundamentally changing the frequency and intensity of wildfires in many places in the US and around the world.

Western US wildfires on the rise

Wildfires in the western United States are getting worse.

While fire is a natural and essential part of these ecosystems, warming temperatures and drying soils—both tied to human-caused climate change—have contributed to observed increases in wildfire activity. The earlier snowmelt and higher temperatures—and resulting drier soils from increased evaporation—in addition to greater water loss from vegetation have contributed to lengthening the Western fire seasons. Leaders at CalFire even suggest there’s not a wildfire “season” at all anymore, as California in recent years has been battling blazes year-round.

Factors unrelated to climate change affect wildfire risk as well. Past fire suppression and forest management practices have also led to a build-up of flammable fuel wood, which increases wildfire risks. The risk to people and property is also rising because of the increasing number of homes and businesses being built in and near wildfire-prone areas known as the “wildland-urban interface.”

In addition, increased tree mortality due to bark beetle infestation—which has underlying climate drivers—has also modified landscapes in ways that make them more likely to burn. Multi-year drought and precipitation patterns also contribute to the growth of low vegetation that is prone to combustion when dry, serving as kindling for larger fires.

Alaska wildfires

In Alaska, where temperatures are increasing twice as fast as the rest of the country, wildfires have been increasing in frequency and size, even though these forests evolved with fire. Four of the ten largest fire years on record have occurred in the past 15 years, burning over 2 million acres in each of those large fire years.

Southeastern US wildfires

Fire patterns and behavior are also changing in the southeastern United States, where historically fire-adapted ecosystems have undergone massive transformations due to pathogens like chestnut blight, insects like the hemlock woody adelgid, and widespread drought.

The Southeast is one of the largest areas in the United States burned by prescribed fires and has the highest number of wildfires. In the fall of 2016, a four-month seasonal drought combined with accumulated plant material and higher temperatures created the worst wildfire that the southern Appalachians had seen in a century.

With droughts like the one in 2016 expected to increase in frequency, our Southeastern ecosystems may transform drastically. In these forests, prescribed burns are being used more frequently and successfully, proactively reducing the incidence of large and devastating wildfires.

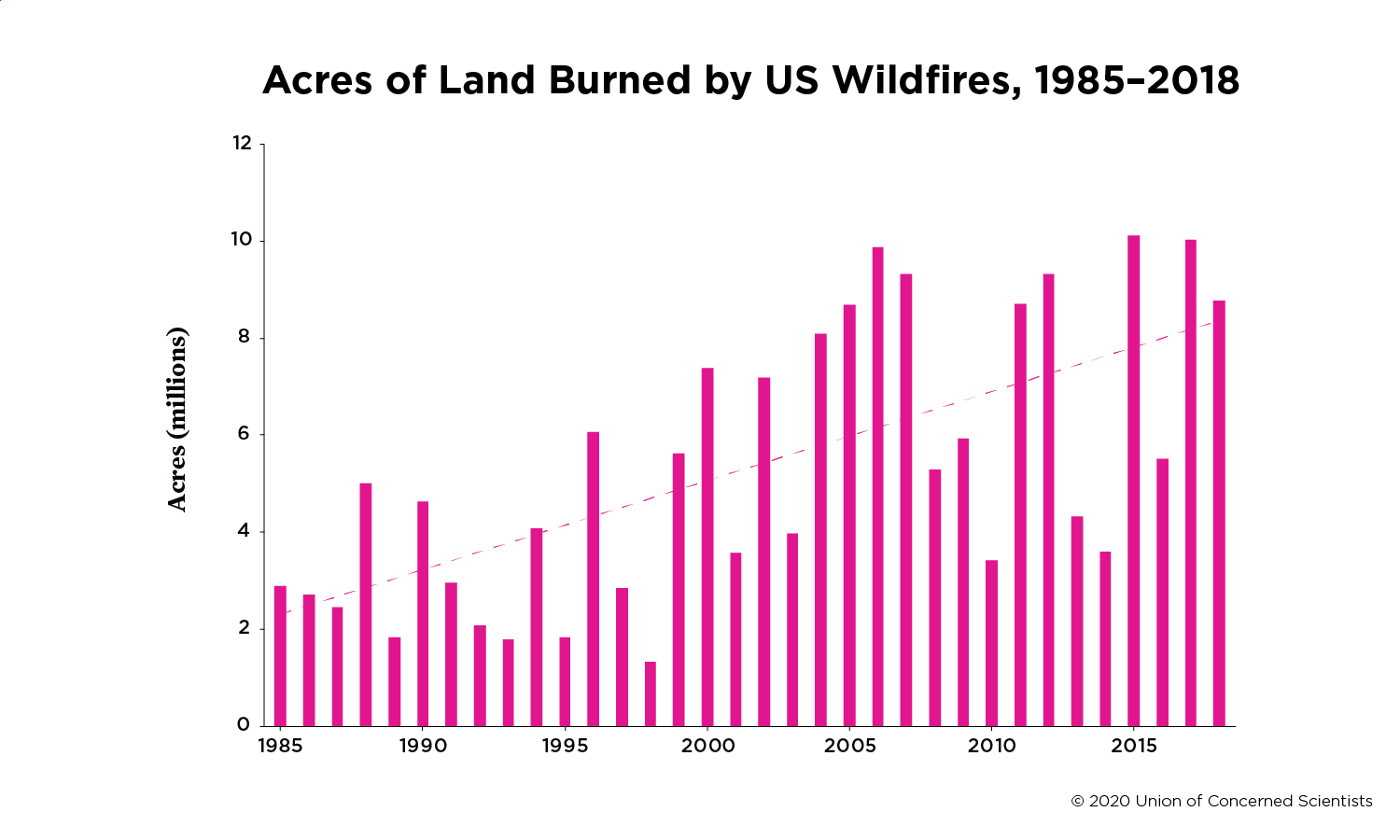

US wildfires overall

For the United States as a whole, the total number of acres burned by wildfires and the average acres burned per fire has been ticking up in recent decades (see figure above). From 2000 to 2018, wildfires burned more than twice as much land area per year than those from 1985 to 1999.

As the climate continues to warm, wildfires are likely to remain a risk over the next few decades. We must take action to improve forest and fire management practices and reduce our reliance on fossil fuels to limit the risks of worsening wildfires.

To help protect people and property, as well as manage forest and fire, practices must be updated to reflect the latest science. Investing in adaptation measures, such as limiting development and implementing fire-resilient measures for existing communities in fire-prone areas, can help reduce the danger of wildfires. Smoke from wildfires can travel for miles and poses a serious risk to public health, especially for young children and those who may have heart and lung ailments, making early warning systems and health-protective measures vital.

Measures to climate-proof our infrastructure—especially our power grid—are also necessary. We can achieve this by increasing local technical capacity and incorporating costs of climate change and benefits of climate resilience into economic assessments, and develop data and tools for analyses.

Perhaps most importantly, we must sharply curtail the global warming emissions that are fueling climate change and increasing wildfire risks.