Table of Contents

As our climate continues to heat up and the impacts of that warming grow more frequent and severe, farmers and farm communities around the world will be increasingly challenged. And US farmers won’t be spared the damage that climate change is already beginning to inflict.

In fact, the industrial model that dominates our nation’s agriculture—a model that neglects soils, reduces diversity, and relies too heavily on fertilizers and pesticides—makes US farms susceptible to climate impacts in several ways.

The combination of advancing climate change and an already-vulnerable industrial system is a “perfect storm” that threatens farmers’ livelihoods and our food supply. The good news is that there are tools—in the form of science-based farming practices—that can buffer farmers from climate damage and help make their operations more resilient and sustainable for the long term. But farmers face many obstacles to changing practices, so it’s critical that policymakers shift federal agriculture investments to support and accelerate this transition.

How climate change will challenge farmers

Various authoritative reports, most notably the multiagency 2018 Fourth National Climate Assessment, have reviewed what science is telling US farmers to expect in coming decades—and it’s not pretty.

Climate change trends

Changing precipitation patterns. Rainfall patterns have already begun shifting across the country, and such changes are expected to intensify over the coming years. This is likely to mean more intense periods of heavy rain and longer dry periods, even within the same regions.

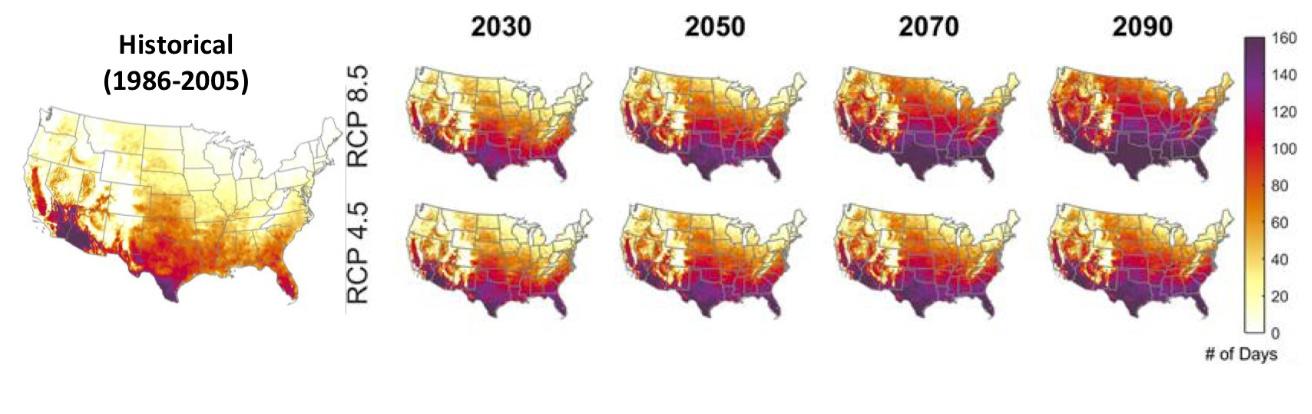

Changing temperature patterns. Rising average temperatures, more extreme heat throughout the year, fewer sufficiently cool days during the winter, and more frequent cold-season thaws will likely affect farmers in all regions.

Climate change impacts

Floods. We’ve already seen an increase in flooding in many agricultural regions of the country, including the Midwest, the Southern Plains, and California. Sea level rise is also ratcheting up the frequency and intensity of flooding on farms in coastal regions. These costly floods devastate crops and livestock, accelerate soil erosion, pollute water, and damage roads, bridges, schools, and other infrastructure.

Droughts. Too little water can be just as damaging as too much. Severe droughts have taken a heavy toll on crops, livestock, and farmers in many parts of the country, most notably California, the Great Plains, and the Midwest, over the past decade—and science tells us that rising temperatures will likely make such droughts even worse, depleting water supplies and, in some cases, spurring destructive wildfires.

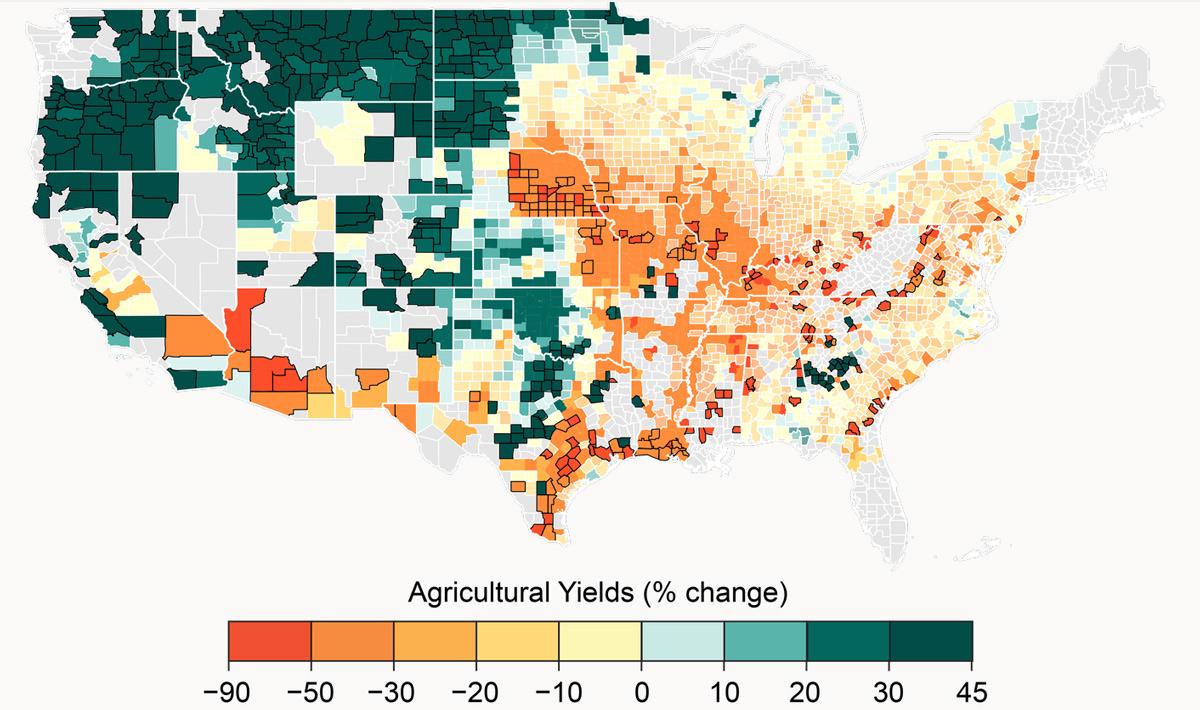

Changes in crop and livestock viability. Farmers choose crop varieties and animal breeds that are well suited to local conditions. As those conditions shift rapidly over the coming decades, many farmers will be forced to rethink some of their choices—which can mean making new capital investments, finding new markets, and learning new practices.

New pests, pathogens, and weed problems. Just as farmers will need to find new crops, livestock, and practices, they will have to cope with new threats. An insect or weed that couldn’t thrive north of Texas in decades past may find Iowa a perfect fit going forward—and farmers will have to adapt.

Industrial amplifiers

Degraded soils. Typical monoculture cropping systems leave soil bare for much of the year, rely on synthetic fertilizer, and plow fields regularly. These practices leave soils low in organic matter and prevent formation of deep, complex root systems. Among the results: reduced water-holding capacity (which worsens drought impacts), and increased vulnerability to erosion and water pollution (which worsens flood impacts).

Simplified landscapes. Industrial agriculture treats the farm as a crop factory rather than a managed ecosystem, with minimal biodiversity over wide areas of land. This lack of diversity in farming operations exposes farmers to greater risk and amplifies climate impacts such as changes in crop viability and encroaching pests.

Intensive inputs. The industrial farm’s heavy reliance on fertilizers and pesticides may become even more costly to struggling farmers as climate impacts accelerate soil erosion and increase pest problems. Heavy use of such chemicals will also increase the pollution burden faced by downstream communities as flooding increases. Farmers may also increase irrigation in response to rising temperature extremes and drought, further depleting precious water supplies.

What it will mean

How will these industrially amplified climate change impacts affect people—farmers, residents of rural communities, and all of us who rely on the food farmers produce? In a variety of ways:

- As summer heat intensifies, farmers and farm workers will face increasingly grueling and potentially unsafe working conditions.

- Accelerating crop failures and livestock losses will make farmers with access to insurance or disaster relief programs more reliant on those taxpayer-funded supports, while those without sufficient safety nets will face additional challenges. Failing farms and stagnating farm profits will also increase suffering in many rural communities.

- Farming communities will be among the first to feel the ways extreme weather exacerbates agriculture’s impacts on water resources—with nearby water supplies polluted or depleted before the damage extends to drinking water and fisheries far downstream.

Nationwide, reductions to agricultural productivity or sudden losses of crops or livestock will likely have ripple effects, including increased food prices and greater food insecurity.

Meeting the challenge

Business as usual won’t protect the future of our food supply—or the well-being of the farmers and communities that produce it. We need to take concrete steps to prepare for climate impacts on agriculture and to reduce both their severity and our vulnerability to them.

We also need to remember that climate change risks aren’t distributed equally—and neither are the pathways to climate adaptation. Public policies and institutional practices have long denied communities of color, low-income groups, and tribal communities access to critical resources and decision-making processes, leaving them with fewer options and more risk in the face of climate impacts. So it’s crucial to ensure that these communities have a voice in shaping our adaptation strategies.

Helping farm communities manage severe impacts

When climate impacts strike, support systems need to be in place to help communities cope and recover:

Shelters and other facilities to provide housing, food, first aid, and other immediate needs for people whose lives have been disrupted or displaced by floods, droughts, fires, or storms.

Investment in local capacity and infrastructure to support people harmed by climate impacts as they rethink or rebuild their lives and businesses. This includes not only infrastructure for communication, transportation, water and sanitation, but also training in new practices and opportunities that build adaptive capacity.

Reducing damage by making farms more resilient

Our farms and farm communities don’t have to be sitting ducks for climate impacts. Forward-looking farmers and scientists are finding new, climate-resilient ways to produce our food:

Build healthier, “spongier” soils through practices—such as planting cover crops and deep-rooted perennials—that increase soil’s capacity to soak up heavy rainfall and hold water for dry periods;

Make farms stronger by redesigning them as diverse agroecosystems—incorporating trees and native perennials, reducing dependence on fertilizers and pesticides, and reintegrating crops and livestock;

Develop new crop varieties, livestock breeds, and farm practices specifically designed to help farmers adapt to evolving climate realities.

Addressing the root of the problem

Finally, whatever we do to help farmers adapt to climate change, we still face the urgent need and obligation to reduce the source of the problem as far and as fast as we can. This means bringing net emissions of heat-trapping gases down to zero, and doing it soon.

Fortunately, our farm and food system can be an important part of the solution, both by reducing emissions at every stage of the food production and distribution process, and by building agroecosystems that can sequester (store) more carbon.

Policy recommendations

What policy levers can we pull to help get these solutions off the ground?

Invest in public research. Publicly funded research provides farmers with the tools and information they need to maximize efficiency and productivity. With climate change, farmers need science more than ever, yet public funding for research that can help them cope has been in short supply. Agroecology research—which produces the kind of long-term, literally root-deep solutions that can help farms stay viable for generations—has been particularly underfunded.

Expand conservation programs in the federal farm bill that make it easier for farmers to adopt sustainable practices that will make their farms more climate-resilient. We need to boost their funding and their impact.

Strengthen safety nets (and make them drivers of resilience). Regardless of what science and forward-looking policy can do, farms across the country will be challenged—and some more than others. It’s essential that we provide farm families and communities with the support they need to survive the climate crisis and become more resilient. This includes better crop insurance programs, health care access for farmers and farm workers, and effective, responsive disaster relief programs.

Achieve net zero emissions. We need to prioritize policies to drastically reduce our climate emissions and give us a chance of getting to net zero ASAP. Reversing the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement would be a good start, but there is much more we can do.